10 Microorganisms and Pathogens That Help Treat Diseases

It might seem paradoxical that diseases and pathogens, often viewed as harmful, can be used to treat other illnesses. However, medical science has discovered numerous surprising ways that microorganisms, ranging from bacteria and viruses to fungi and protozoa, can help combat some of the most deadly diseases known to humankind.

These treatments may seem strange at first glance, but they have led to remarkable medical breakthroughs.This article delves into 10 fascinating microorganisms and pathogens that have been harnessed in the battle against disease, offering insight into the intriguing world of microbial medicine.

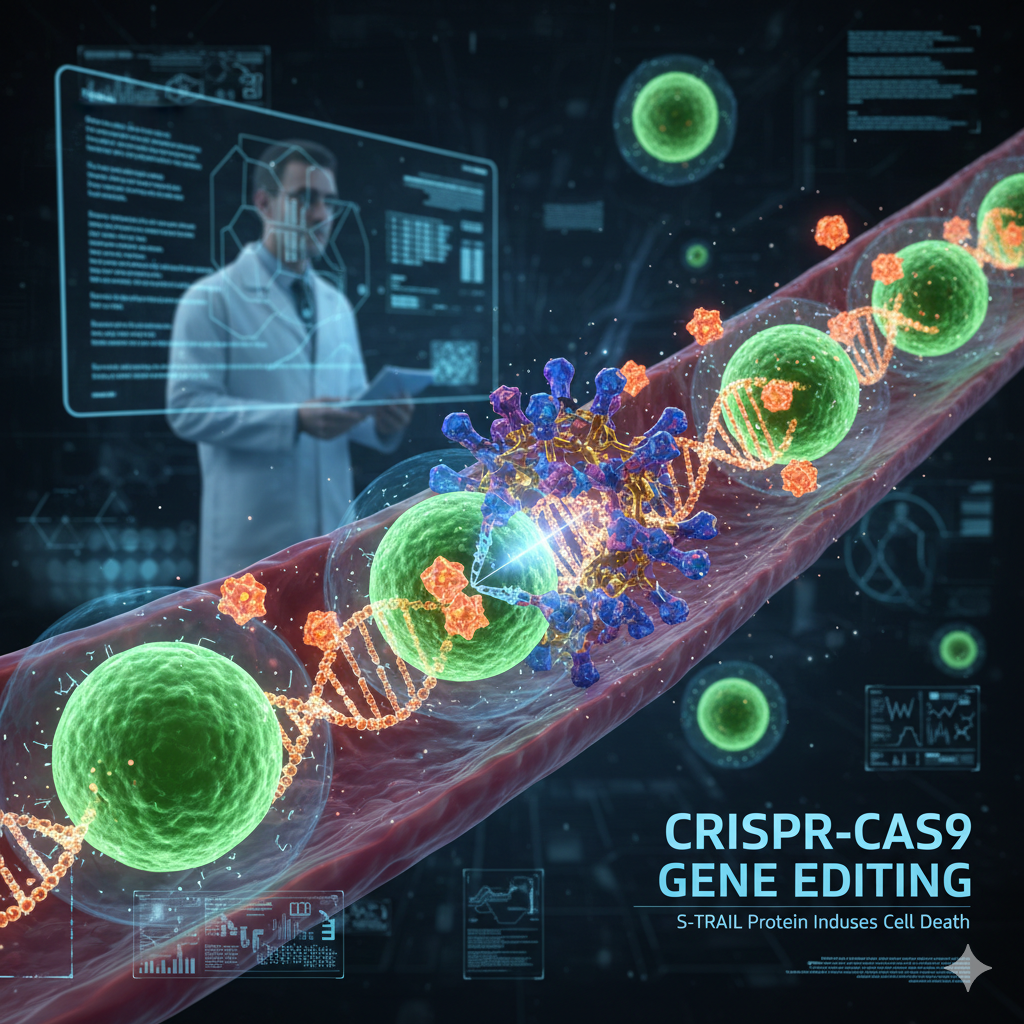

Cancer Treatment

Cancer treatment has traditionally relied on surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. However, a new frontier has emerged in the form of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology.

CRISPR, which stands for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,” allows scientists to target and modify the DNA of living organisms. For cancer, CRISPR offers an innovative approach to directly edit cancerous genes within the body’s cells.

Researchers at the Rutgers Cancer Institute in New Jersey have been experimenting with CRISPR to inject cancerous cells with S-TRAIL protein. This protein kills surrounding cancer cells by inducing cell death, effectively targeting tumors.

The process has shown significant promise in laboratory settings, particularly when used to treat hard-to-target cancerous cells circulating through the bloodstream, though testing is still in its early stages.

The potential for CRISPR-based cancer treatments is immense, with applications ranging from targeting specific tumor markers to modifying the immune system’s response to cancer cells.

As research progresses, CRISPR may soon become a staple in the fight against various forms of cancer, offering precision medicine that was previously unimaginable.

Cowpox

Smallpox, one of the deadliest diseases in human history, claimed millions of lives worldwide before it was declared eradicated in 1980.

The breakthrough in smallpox vaccination came when Dr. Edward Jenner, in the late 18th century, observed that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox, a mild disease, did not seem to get smallpox. This led to the development of the first smallpox vaccine, using the cowpox virus.

The success of Jenner’s cowpox-based vaccine heralded the beginning of modern immunology. The vaccination derived from the vaccinia virus, closely related to cowpox, was instrumental in wiping out smallpox globally.

Jenner’s work laid the foundation for the global vaccination programs that have saved countless lives and continue to protect humanity from deadly infectious diseases.

Today, the cowpox vaccine serves as a symbol of how a virus that poses little threat to humans can be leveraged to eradicate more dangerous diseases. The continued evolution of vaccine science is rooted in Jenner’s discovery, proving the profound impact of microorganisms on human health.

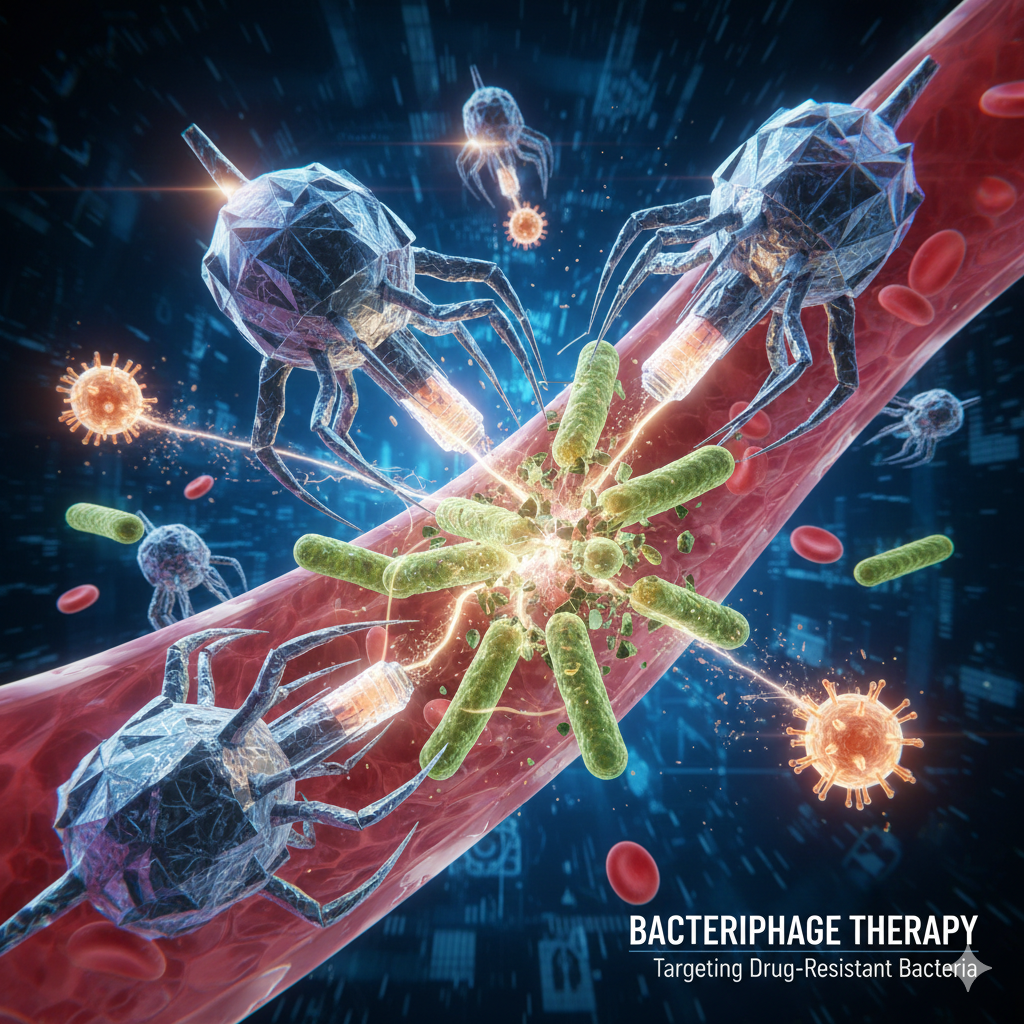

Bacteriophage Therapy

Bacteriophages, or “bacteria-eating viruses,” are viruses that specifically target and destroy bacteria. While antibiotics revolutionized medicine in the 20th century, the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has spurred renewed interest in bacteriophage therapy as an alternative treatment.

These viruses can selectively attack harmful bacteria, leaving beneficial microorganisms in the body unaffected.

The potential for bacteriophage therapy was demonstrated in 2015 when doctors successfully used this treatment to save the life of Tom Patterson, a patient infected with drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

Traditional antibiotics had failed, but bacteriophage therapy proved effective in treating his infection. This case has rekindled interest in bacteriophages as a viable treatment for superbugs, bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics.

Researchers are now exploring the potential of bacteriophages in treating a range of bacterial infections, from tuberculosis to pneumonia, marking a significant step forward in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

HIV-Based Gene Therapy

HIV, often associated with the immune system’s decline, has been found to have an unexpected application in gene therapy. In 2010, a team of Italian researchers led by Dr. Luigi Naldini used a modified form of HIV to deliver genetic material into cells, effectively treating children suffering from Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and leukodystrophy, two deadly genetic disorders.

The modified HIV virus acted as a viral vector, carrying the necessary genes to correct the underlying genetic mutations causing these conditions.

The success of this approach demonstrates the incredible potential of viral vectors derived from HIV to treat other diseases, including those affecting the nervous and immune systems.

While the therapy is still undergoing clinical trials, its success in a small group of patients is a significant breakthrough that could offer hope for many families facing genetic disorders with no current treatment options.

Predatory Bacteria

Predatory bacteria, such as Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, have been discovered to consume other harmful bacteria.

This natural predation can be harnessed as a potential treatment for bacterial infections, particularly those caused by antibiotic-resistant strains. These bacteria breach the cell walls of their prey, consume their innards, and then reproduce, attacking other bacterial cells in the process.

Scientists have explored the use of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus to target dangerous bacteria like Shigella, responsible for severe food poisoning.

In laboratory tests, the predatory bacteria significantly reduced Shigella populations, offering hope for new treatments to combat the global threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Researchers are now looking into the application of predatory bacteria to treat infections caused by Salmonella and E. coli, potentially providing a sustainable and effective treatment for superbugs.

Poliovirus

Poliovirus, notorious for causing polio, has been genetically modified and repurposed to target glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer.

The modified poliovirus, known as PVSRIPO, is injected directly into the brain tumor, where it seeks out and destroys cancer cells. This innovative approach to cancer treatment was developed by researchers at Duke Cancer Institute in North Carolina.

Clinical trials have shown promising results, with a survival rate of 21% for glioblastoma patients treated with PVSRIPO, compared to just 4% for those receiving conventional treatments.

Although still in its experimental stages, this treatment represents a novel approach to treating one of the deadliest types of cancer.

Coley’s Toxin

Coley’s toxin, named after Dr. William Coley, is a cancer treatment that uses bacteria to stimulate the immune system. Dr. Coley observed that patients who contracted bacterial infections after cancer surgeries seemed to experience remission, leading him to hypothesize that bacterial infections could boost the immune system’s ability to fight cancer.

Although the use of live bacteria was eventually replaced by antibiotics, Coley’s toxin treatment remained influential.

Today, scientists use genetically modified bacteria in cancer treatments, drawing on Coley’s pioneering work. While the results were mixed in his time, the theory behind Coley’s toxin still holds promise, particularly in the context of immune therapies for cancer.

Maraba Virus

The Maraba virus, a naturally occurring virus, has been found to destroy cancer cells. But more recently, researchers have discovered its potential to target and destroy HIV-infected cells.

Unlike antiretroviral drugs, which only suppress active HIV cells, the Maraba virus can attack dormant HIV cells, offering a potential cure for HIV.

Lab tests have demonstrated the Maraba virus’s effectiveness in destroying dormant HIV cells. Though the virus has not been tested in humans or animals, it represents an exciting new approach to HIV treatment. If successful, it could revolutionize the way we treat this virus, offering hope to millions worldwide.

Malaria as a Treatment for Syphilis

In the early 20th century, Austrian psychiatrist Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg discovered that malaria could be used to treat syphilis. By inducing a high fever with malaria, Dr. Wagner-Jauregg was able to kill the bacteria causing syphilis.

Although the method had risks, such as the potential for malaria to become life-threatening, it was effective in curing syphilis until the advent of antibiotics.

While the method had remarkable success, it came with significant risks. Patients could suffer from severe complications such as kidney failure and anemia, and the strain of malaria used was highly dangerous. Eventually, this treatment was replaced by antibiotics, but Dr. Wagner-Jauregg’s work remains a significant milestone in medical history.

CAR-T Therapy

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy is a groundbreaking cancer treatment that uses the patient’s own immune cells to fight cancer. In CAR-T therapy, T-cells are extracted from the patient’s blood, modified to target cancer cells, and then reintroduced into the body to attack and destroy the tumor.

CAR-T therapy has shown great promise in treating certain cancers, including leukemia and lymphoma. However, the therapy is still considered a last resort due to its complex and time-consuming nature.

Despite the potential for side effects, including brain inflammation, CAR-T therapy is a significant step toward personalized cancer treatments that are tailored to each individual’s needs.

Conclusion

The use of microorganisms and pathogens to treat diseases represents a fascinating and often counterintuitive approach to modern medicine.

From CRISPR gene editing to the use of viruses like the Maraba virus, scientists are continually discovering new ways to harness the power of these microorganisms to fight diseases that were once thought incurable.

While some of these treatments are still in experimental stages, the potential they hold is immense, offering hope for patients with conditions that have resisted traditional treatments for years.

As research progresses and these innovative therapies become more widely available, we may see a future where the boundaries between “disease” and “cure” are not so easily defined.

The lessons learned from these microorganisms and pathogens will undoubtedly pave the way for even more groundbreaking treatments, providing patients with new options for managing and even curing some of the world’s deadliest diseases.