10 Alarming Issues Linked to Genetically Modified Foods

I still recall the early promises of genetically modified foods, that science would feed the world, reduce pesticide use, and make farming more efficient. It sounded compelling. Yet in 2025, as GMOs (genetically modified organisms) and gene‑edited crops become more widespread, real problems are already unfolding. These issues aren’t just theoretical anymore; they’re being felt in fields, ecosystems, markets, and communities around the globe.

In this article, I explore 10 significant problems that genetic modification in food and crops is already causing. I draw on the latest scientific research, environmental observations, socio‑economic reports, and ongoing public debates. This is not outdated commentary; this is what the evidence shows right now, and what’s driving both policy shifts and public concern in 2025.

The Hidden Environmental Toll

- fewer wild plants and flowering weeds that support pollinators

- decreased soil microbial diversity

- reduced resilience in surrounding ecosystems

Extensive research continues to show that intensive GM crop farming can reshape soil chemistry and microbial communities, with long‑term ecological effects that aren’t yet fully understood.

Superweeds and Escalating Herbicide Use

Yes. One of the biggest practical challenges has been the rise of “superweeds”— weed species that have evolved resistance to common herbicides due to repeated use on herbicide‑tolerant GM crops.

- more herbicide use

- more resistant weed species

- greater environmental harm

- increased cost for farmers

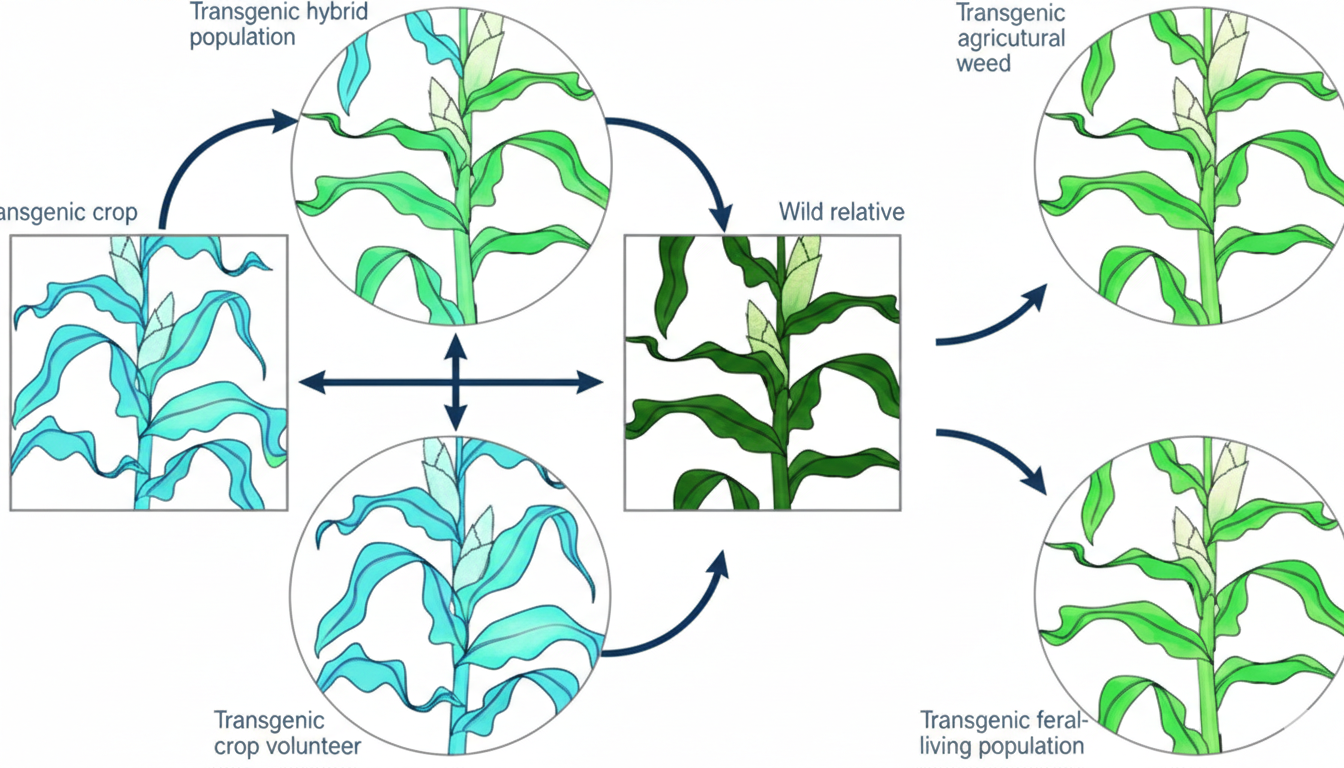

Gene Flow and Threats to Wild Plant Populations

One of the most underappreciated science‑based concerns is gene flow, the transfer of engineered traits from GM crops into wild plant populations. This can occur through pollination or seed dispersal, and once a transgene escapes, it’s effectively irreversible.

Human Health Considerations

In 2025, the scientific consensus remains that approved GMO foods currently on the market are generally safe for human consumption, and there is no compelling evidence linking them directly to cancer or widespread health harm.

- The potential for GM proteins to cause allergic reactions

- The theoretical risk of new or unexpected allergens appearing

- Debate over indirect exposures (e.g., through herbicides or pesticide residues)

For example, some research warns that, without careful screening, a genetically introduced protein could trigger allergic responses in susceptible individuals, even when it is rare.

The overall picture is nuanced: the technology itself isn’t inherently harmful, but its products must be carefully and continuously assessed, especially as new traits emerge.

Economic and Seed Sovereignty Problems

- farmers can no longer save seed from one season to the next

- Input costs rise as seeds must be repurchased

- market power becomes concentrated in corporate hands

Some emerging technologies, like genetic use restriction technologies (GURTs), could further cement dependence on commercial seeds, impacting both cost and biodiversity, though these technologies have not yet been commercialized due to opposition.

Regulatory Gaps and Global Inconsistencies

Regulatory approaches to GMOs vary widely worldwide, from strict scrutiny in the European Union to more permissive systems in the United States. Scientific reviews of regulatory frameworks emphasize that while safety assessments are robust for commercialized GMOs, long‑term ecological monitoring is limited and inconsistent.

Public Trust Erosion and Consumer Anxiety

Surveys consistently reveal significant public skepticism around GMO foods, particularly regarding health impacts, transparency, and labeling. Many consumers worldwide support clear labeling so they can make informed choices about what they eat.

Herbicide Residues

While the World Health Organization and many regulatory bodies consider existing GMO crops safe, a major debate persists over herbicides associated with some of those crops, especially glyphosate.

Glyphosate has been classified as a probable human carcinogen in certain classifications and remains controversial due to its widespread use and potential effects at higher exposure levels.

Biodiversity Erosion and Cultural Heritage Concerns

Across many regions, traditional crop varieties are disappearing. In places like Colombia, smallholder and Indigenous farming communities are actively resisting GMO seeds to protect native seed varieties and cultural heritage.

Ecological Dependence: Pesticide and Input Intensification

Contrary to early promises, many GM crops have not consistently reduced pesticide use. While some varieties (like Bt crops) can reduce specific insecticide applications, herbicide‑tolerant crops often require heavier chemical use to control resistant weeds — contributing instead to input intensification.

Conclusion

By 2025, genetically modified foods and crops have moved far beyond a hypothetical future, they’re part of our global food system. Yet many real problems are already clear, and the conversation is no longer just scientific: it’s cultural, economic, and political.

- GM food technology is not inherently harmful, but its impacts must be evaluated on a case‑by‑case basis.

- Environmental concerns, including biodiversity loss and chemical escalation, are tangible and documented.

- Economic and seed sovereignty issues are reshaping rural livelihoods and farmer autonomy.

- Public trust remains a critical factor in shaping the future of genetically modified food policy.

- Long‑term monitoring and global regulatory coordination are still evolving.

The future of food lies not in ignoring these challenges, but confronting them with transparent science, robust regulation, and respect for both environmental and societal values.